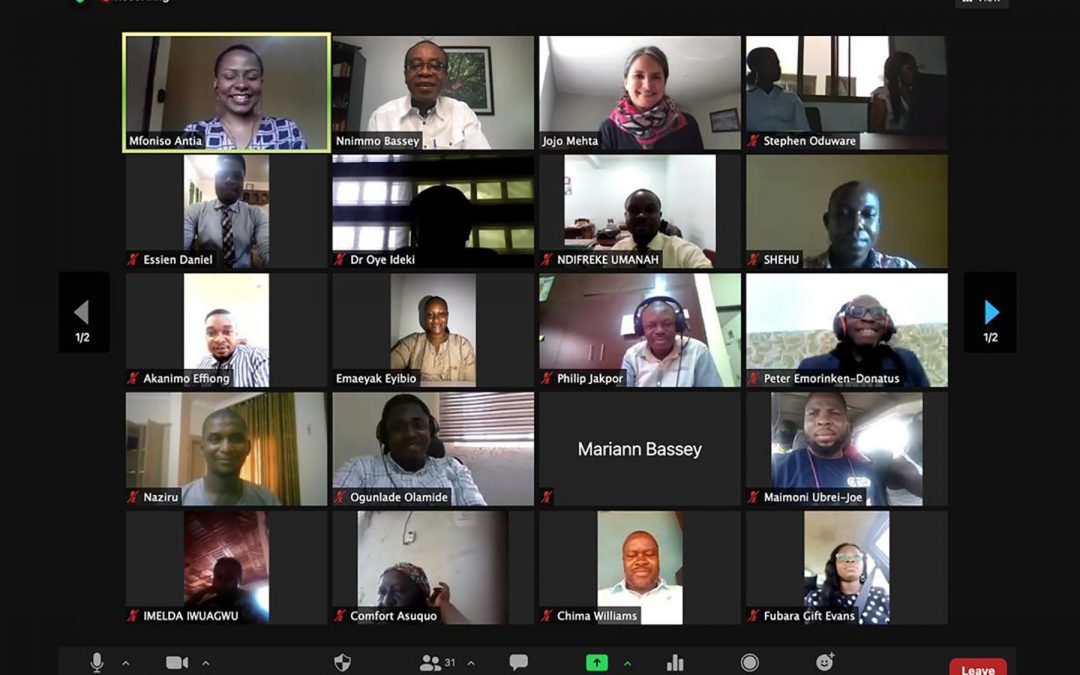

A movement is growing around the world to make ecocide a crime at the International Criminal Court (ICC). With the mounting global movement, a lot of information about ecocide is now in the public domain. However, Health of Mother Earth Foundation (HOMEF) observed that many of her stakeholders are yet to fully understand the enormous potential for systemic change that the championed ecocide law will bring. To fill the observed knowledge gap, HOMEF on 24 May 2021 held a virtual Conversation series with the title “Ecocide: The Crime and the Law.

Jojo Mehta who is the executive director of Stop Ecocide International which she co-founded with late barrister Polly Higgins (an inspiring figure in the movement) was invited to lead the Conversations. Jojo Mehta is also the convenor of the Independent Expert Panel for the Legal Definition of Ecocide. She informed participants at the Conversations that the expert panel which is currently concluding work on the legal definition of ecocide has 12 members. These members are from different parts of the world including Africa (Serra Leone and Senegal), with a mixture of international criminal lawyers and environmental lawyers. The panel plans to complete the drafting process of the legal definition in June 2021 and then launch the definition publicly with a press conference in same June.

The legal definition was said to be necessary for specific reasons which are to: gain countries’ support (as it is what countries would look at to be able to support the law); fit into the Rome Statute; get a definition serious enough to warrant the place of an international crime and; that is not so high that it becomes impossible to prosecute for the crime.

Nnimmo Bassey, director of HOMEF, situated ecocide law as “a key potential solution to addressing the climate and ecological crises as well as other harms that are being inflicted on Mother Earth by various actors.”

Jojo Mehta presented a working definition of ecocide as “mass damage and destruction of ecosystems that is systematic and is committed with knowledge of the risks.” According to her, “the definition makes it impossible for the perpetrators of serious destruction of nature to say they did not know what the results of their actions and activities might be.”

The Conversations interrogated why ecocide was not included in the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court which was adopted on 17 July 1998 and has so far been acceded to by about 123 countries including Nigeria. Responding, Jojo Mehta stated that “at the time of the drafting of the Code which became the Rome Statute, the governing document of the ICC, there was a clause which covered serious environmental destruction. That clause was dropped without a vote before the Statute was agreed upon.” She explained that reasons for dropping the clause may be connected to objections by the United States of America, United Kingdom, the Netherlands and France as well as to the investigation and development of nuclear testing at the time (the 1990s). “Polly Higgins came about the missing clause while carrying out research around the possibility of criminalising ecosystems’ destruction” Jojo Mehta informed.

If the clause had made it to the Rome Statute 20 years ago, ecocide would have for long appeared in international law as an international crime and probably the increasing ecosystems’ destruction experienced today may have been nipped in the bud. For example, some countries may have been prosecuted for nuclear testing, especially in the Pacific, which had devastating impact that is still felt today. Nnimmo Bassey decried the fact that some countries knowingly used territories far away from home to test nuclear weapons showing the intent to externalize the harms to other people. These are some of the issues that ecocide law begs to tackle.

The reasons why ecocide is championed as an international crime and law were brought to the table at the Conversations. First, in terms of ecological deterioration, what we are facing in the world is a global lethal crisis with different parts of the world facing different degrees and kinds of sufferings due to ecocide. Hence, bringing ecocide to the international level is more practical as the world needs to move together to tackle the climate and environmental crises affecting all. Also, with ecocide criminalised at the international level, any state that has ratified it can prosecute for that crime. Jojo Mehta pointed out that the ICC cannot override a sovereign states’ decision to ratify a crime or not. But by the international nature of the crime and by universal jurisdiction principles, the crime of ecocide can be prosecuted by any ratifying state where the offender/accused has physical or operational presence. This goes to show that the scope for the potential of prosecution for ecocide is brother than what is obtainable for some other international crimes.

Second, politically speaking, it is much easier for states to express support for an international law knowing that lots of states need to come on board for such a law to move forward.

Third, criminalising ecocide at the international level removes corporate impunity and prevents jurisdiction hopping, a situation where companies simply move operations to a different country to escape punishment. This is because focus is rather on the key decision makers behind the ecocidal projects. And these set of persons are often in the wealthy North.

Fourth, ecocide as an international crime and law will lead to the shifting of cultural mindsets and will send a very strong moral message. It will shift the normative and put carelessness about damage to nature below the moral red line. It will also represent a deep fundamental shift, serving both as a deterrent and as an empowering instrument for activists, NGOs, academics, scientists and all others working towards more responsible relationship with nature.

Jojo Mehta was optimistic that within three to five years, it is possible to get the ecocide law in place. This is possible considering the momentum building up for criminalising ecocide, increased level of awareness due to exposure to information from the internet and of public pressure on the issue. It was reported during the Conversations that eight ICC member countries have a recorded interest at government level in making ecocide an international crime. The countries include- Vanuatu and the Maldives, France, Belgium, Spain, Finland, Canada and Luxembourg. Also, there are different countries where the conversation on ecocide has been brought to life at the parliamentary level. Fifteen other countries were said to have shown interest in the legal definition of ecocide being evolved. In May 2021, two votes in the European parliament supporting in principle the criminalisation of ecocide emerged. His Holiness Pope Francis had also publicly raised the issue of ecocide at the International Association of Penal Law in Rome, specifically calling for it to be made a fifth crime against peace at the ICC.

Again, the Rome Statute is now said to have a simple amendment procedure ensuring that if enough support can be achieved from member states the crime can move to the ICC.

The optimism for criminalising ecocide internationally also flowed from governments’ increasing capacities to act fast considering the quick actions they have been able to take regarding COVID-19 policies and regulations. The discussants agreed that the political world now has to expand their ability to act fast in addressing all sorts of ecological and climate crises.